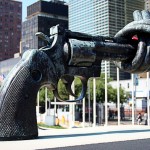

Arms Trade Treaty negotiations failed. And the integral disarmament seems to be so far away

«The governments’ efforts will be judged by how many lives the treaty helps to save.» Christian leaders representing some of the world’s two billion Christians have issued a joint appeal to the 194 governments that negotiated the first global Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). But this appeal remained unlistened. Having started on 2 July, the UN Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty concluded Friday . The negotiations on an Arms Trade Treaty have been called off after governments were not able to reach agreement on international regulation of arms exports. The negotiations so failed to establish the first international treaty meant to regulate the multi-billion-dollar arms trade. U.N general secretary Ban Ki Moon said he was «disappointed» the member states failed to clinch an agreement after years of preparatory work and four weeks of negotiations, calling it a «setback»; some member nations blamed the United States for halting an agreement at the end of the month-long negotiations in New York. – and U.S. State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland answered in a statement that while the U.S. had wanted to conclude the negotiations with a treaty, «more time is a reasonable request for such a complex and critical issue» –; and the World Council of Churches’ general secretary Rev. dr. Olav Fykse Tveit maintained that «Churches are concerned with the postponement in this long process, but we will plead for stronger controls of conventional weapons for a more peaceful and just world. Recent conflicts in several countries show the need for that».

«The governments’ efforts will be judged by how many lives the treaty helps to save.» Christian leaders representing some of the world’s two billion Christians have issued a joint appeal to the 194 governments that negotiated the first global Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). But this appeal remained unlistened. Having started on 2 July, the UN Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty concluded Friday . The negotiations on an Arms Trade Treaty have been called off after governments were not able to reach agreement on international regulation of arms exports. The negotiations so failed to establish the first international treaty meant to regulate the multi-billion-dollar arms trade. U.N general secretary Ban Ki Moon said he was «disappointed» the member states failed to clinch an agreement after years of preparatory work and four weeks of negotiations, calling it a «setback»; some member nations blamed the United States for halting an agreement at the end of the month-long negotiations in New York. – and U.S. State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland answered in a statement that while the U.S. had wanted to conclude the negotiations with a treaty, «more time is a reasonable request for such a complex and critical issue» –; and the World Council of Churches’ general secretary Rev. dr. Olav Fykse Tveit maintained that «Churches are concerned with the postponement in this long process, but we will plead for stronger controls of conventional weapons for a more peaceful and just world. Recent conflicts in several countries show the need for that».

Vatican sidelined

Churches commitment for the ATT was strong. The last week WCC joint appeal reminded all that saving human lives is the most visible and concrete aim of the ATT. And saving human lives is the reason why the Holy See – which has always been committed to policies and negotiations for disarmament – decided to take part in the drafting of the ATT. In the end, the Treaty is the «least bad» solution, a hurdle on the path to integral disarmament, which is the great utopian ideal of the Church. A «utopian ideal» that is not an unreachable goal: on the basis of the Social Doctrine of the Church and comprehensive human development, step by step, the Holy See’s diplomatic engagement has been able to achieve important milestones. It is a path toward the «disarmament of the heart», the necessary pre-condition to reach full disarmament. In fact, Holy See did not have such a considerable weight in the U.N. conference, because of a tense debate over the seating of a Palestinian representative, which was fiercely opposed by Israel and the US. The Palestinian Liberation Organization has observer status at the UN, as does the Holy See. The dispute was eventually resolved when both Palestinian and Vatican delegates agreed to accept lesser status, making them able to participate in the discussions, but not as recognized members.

ATT, a least bad solution

That the ATT is for the Catholic Church the lesser evil solution is clear in the speeches that Francis Chullikat, Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations, addressed to the Fourth Session of the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty, last February 13th. One of the reasons why the Holy See is a permanent observer – and not a full member – of the United Nations lies on decisions taken on sessions like this. As a full member, the Holy See would be obliged to vote, and its vote could be politically manipulated. As a permanent observer, the Holy See maintains its super partes prerogatives, and at the same time has a considerable diplomatic impact. The Holy See’s main objective is not to have arms considered an «economic good» like any other.

ATT, five Vatican points

Chullikat’s intervention at the committee comprised five points. First, the scope of the ATT, which should be broad, «comprising not solely the 7 categories of arms which the U.N. Register of Conventional Arms considers, but also small arms and light weapons, together with their relevant munitions, which enter the illicit market often with greater ease and give rise to a series of humanitarian problems». Second, the request that the Treaty refer to human rights, humanitarian law and development. At the same time, Chullikat affirms that it is «necessary to find terminology which limits subjective possibilities open to political abuse, and which will facilitate the ascertainment of modalities for application of such criteria».

Chullikat admonished that «the success of the Treaty will depend also on its ability to promote and reinforce international co-operation and assistance between States»; underlined that «provisions relating to assistance for victims must be maintained, and if possible, strengthened, giving attention also to the prevention of illicit arms proliferation, by reducing the demand for arms which often feeds the illicit market». And: «It seems opportune, from this perspective, then, to introduce references in the Treaty to educative processes and public awareness programmes – involving all sectors of society, including religious organizations – that are aimed at promoting a culture of peace.» Finally – Chullikat said – «mechanisms for treaty review and updating need to be strong and credible, capable of quickly incorporating new developments in the subject matter of the ATT, which must remain open to future technological developments. »

On his last interventions to the negotiations in New York, Chullikat re-underlined these five points, remembering that «the ATT debate gave us the opportunity to point out once again the pernicious impact of the illicit arms trade on development, peace, humanitarian law and human rights. Arms cannot simply be compared with other goods exchanged in global or domestic markets. They need a specialised regulation, one capable of preventing, combating and eradicating the irresponsible and illicit trade of conventional arms and related items». Chullikat also said that «this effort calls for the involvement of all members of the international community: States and international organizations, NGOs and the private sector. All of them are responsible for promoting an interrelated action aimed at the “establishment and maintenance of international peace and security with the least diversion for armaments of the world’s human and economic resources” (cfr. Art. 26 of the UN Charter) ».

Arms are not a conventional economic good

The Chullikat’s five points are part of a well defined program. On the one hand, the five points underline the need to diminish the demand for an arms market, favoring peace and education processes instead. In this sense, the Holy See supports the proposal not to allow the issuance of patents to inventions that can be dangerous to human beings. This would make arms production unprofitable, and thus a strong deterrent to the invention and manufacturing of new arms and a good means to get to full disarmament.

On the other hand, it is obvious that favoring peace and education processes means that the Holy See wants more attention paid to people’s development («The new name of peace is development», Paul VI wrote in the encyclical Populorum Progressio in 1967) and to favor the greatest degree possible of multilateral diplomacy, in order to take into account the needs of all countries – even the smallest ones (several times the Holy See has criticized the G-meetings – G8, G20 – and advocated for a reform of the United Nations). It is to protect the poorest countries that the Holy See requested that the Arms Trade Treaty include all arms – and not just the types included in the United Nations Register –in illicit traffic prevention efforts.

Until now, the Holy See was alone in the fight to broaden the Treaty. Only recently the United Kingdom – at the end of the visit of the delegation sent by Prime Minister Cameron to celebrate 30 years of diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and the Holy See – joined the Holy See in this effort. And then also Mexico – during the Papal trip – backed the Holy See positions at the ATT negotiations.

An “intellectual” and economical struggle

The Holy See’s position on disarmament impinges upon, in a very particular way, the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. TRIP is an international agreement administered by the World Trade Organization (WTO) that sets minimum standards for mutual recognition of many forms of intellectual property among member states. It was negotiated at the end of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1994. Article 27.2 of TRIP allows States to withhold patents on inventions which application could threaten public order or human life or health.

Not to patent weapons inventions would make the development of arms less attractive to industries, and States may be less interested in producing and trading them. The risk that technological and scientific progress may be used to elude international regulations on disarmament and arms control, or as a means of economic and military hegemony, remains. Highly developed countries could claim that sophisticated – so called “intelligent” – arms are compatible with disarmament and arms control regulations, and with international human rights. This could lead to a controversial scenario: only the arms held by less developed countries – not as sophisticated – would be incompatible with regulations, i.e. illicit. Another problematic area relates to the development of genetically modified biological weapons, or bio-technological military applications, were rich countries would also have the competitive advantage.

Economic-financial issues always press on. The «civilian» economy tends to overlap with military-driven technological advancements and spending. Much of the concerns of the Holy See have been on dual use, i.e. on the possibility that that the same good could be used for both civil and military purposes. There is a need for clarity, since «dual use» technology can bring confusion to trade regimes unable or unwilling to properly distinguish between the civilian and military applications of a product.

These are some of the key points of the Holy See’s diplomatic engagement on disarmament. The Holy See acknowledges there have been positive developments on disarmament and arms control, and closely monitored the negotiations at the United Nations. The Holy See is also aware that UN negotiations can always get «stuck» because of the resistance of particularly influential States – as happened in the last U.N. conference. But there are also some encouraging developments, like the adoption of the Anti-Personnel Landmines Convention and the Cluster Munitions Convention – conventions adopted out of the context of the Conferences on disarmament.

A new diplomacy reveals that not only States are interested in disarmament

This model for new diplomatic activity shows the application of the Social Doctrine of the Church and the merits of the principle of subsidiariaty. It reveals that not only States, through traditional diplomatic channels, are interested in disarmament. This new diplomacy can also be very appealing to Non Governmental Organizations. Diplomacy inspired by religious belief – it is worth noting – should not be undervalued. In the past, documents like the Pastoral Letter on War and Peace. The Challenge of Peace: God’s promise and our response, released by US bishops in 1983, contributed significantly to the debate on arms control, despite Cold War proliferation dynamics. More recently, bishops’ conferences of Scotland, England and Wales campaigned against the renewal of Great Britain’s Trident nuclear system.

More broadly, the fruits of the Holy See’s diplomatic work are like gems shining in many international documents. For example, the right to assistance for cluster munitions victims was included in the Cluster Munitions Convention thanks to the Holy See’s relentless efforts during the Convention’s drafting in Dublin in 2008 (the Convention was signed in Oslo that same year).

Building upon this history of engagement, the Holy See worked on the ATT in New York, and will keep on working on the new talks on this issue. Reaffirming the perspective of the Social Doctrine of the Church, the Holy See upholds the centrality of the human person. This approach perhaps makes disarmament an even greater challenge. It is, however, an approach that is about the healing of the heart and thus sets a path more conducive to full disarmament and the common good.